Self-Optimization is a Poor Substitute for Individuation

Trying to "hack" our bodies and brains disconnects us from authentic self-connection. Here's why we get hooked (and what we might do instead).

Is there anything more seductive than the idea of self-optimization? The idea that if we could just…get…it…right… we’d have finally have the energy of a happy toddler, the razor-sharp brain of a chess prodigy, the strength and power of a slow-motion Clydesdale shaking its mane in a Budweiser commercial. Or whatever you’d like to imagine.

The cost of my own self-optimization is embarrassingly high. I’ve bought probably thousands of dollars worth of supplements, started countless meal and exercise plans, followed the Huberman protocols1, completed dozens of trainings to certify me in various modalities that I hoped would optimize me and my clients…. 2

And yet, sadly, I remain de-optimized; stubbornly suboptimal. I have the body of a woman in her forties, and the health and energy of someone under a lot of stress, and no “hacking” on my part is going to change that— no matter how much red light/cryo/hyperbaric therapy/Athletic Greens3/NSDR4 I do.

So, okay. The self-optimization project grift has failed me. But what I do have instead, increasingly, is my own autonomy; a grounded sense of my own worth; and an unshakeable connection to my spiritual beliefs.

This, says Jung, is individuation,

“an expression of that biological process – simple or complicated as the case may be – by which every living thing becomes what it was destined to become from the beginning”.5

Seen in this light, individuation sounds to me like the ultimate “self-optimization.” But the two definitions couldn’t be further opposed— and negotiating our way from one to the other is, maybe, the point of our lives.

Self-shame as a survival strategy

I’m going to diverge for a minute to a topic I visit often— because even if you do not identify as someone who has CPTSD or developmental trauma, these concepts are universal human experiences. The “core dilemma” (if you will), is that as children, we have no way of understanding that we are not the center of the world— so if something bad is happening (our parents are divorcing, our teacher is mean, our caregivers are not able to provide us with the resources we need to thrive) our first tendency is to shame ourselves.

This is a strategy that allows small humans to survive what would otherwise be unsurvivable. When our protests fail, we learn to stop asking. When our bodies’ needs aren’t attended to, we learn to disconnect from them. It’s not ideal, but it lets us survive.

Importantly, this strategy also preserves hope, and the idea of love, in our world. We create a fantasy that if we can just manage ourselves properly, we’ll get the love and the care we need. From the child’s perspective, it’s better to see ourselves as “bad” than to accept the idea that our caregivers— and by extension, the universe, God, etc.— are unable to love us as we are.

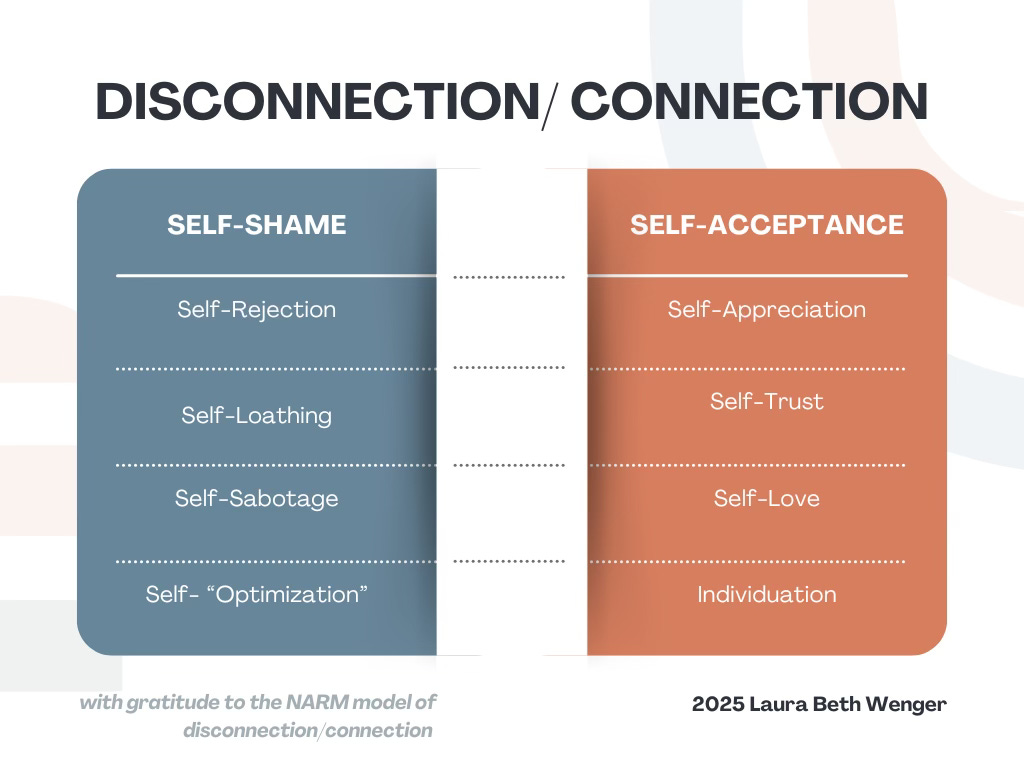

The self-shame trajectory

These childhood survival strategies of self-shaming grow up into adult strategies of self-rejection, self-condemnation, self-loathing, and self-sabotage. They’re perpetuated internally because these beliefs— or, from a Jungian point of view, complexes— are so deeply engrained that we aren’t even aware of them. You could just as easily ask a fish how it feels about water being wet. We don’t know anything else.

They’re especially pernicious in a culture that teaches us that we are responsible for our own well-being. Each of these patterns can be linked to a larger cultural complex, operating seamlessly as interlocking systems and industries and institutions, each of which reinforces our negative self-image and tells us that the only way to improve our lives is through our own efforts.

All these strategies function to keep us disconnected from our natural state of self-connection; self appreciation, authentic self-trust, self-acceptance, self-love. As natural as these states are— no baby is born with shame— they can feel fundamentally wrong, not least because our culture does not encourage us to appreciate our own self-worth. We’ve learned, both as children, and as members of a hierarchical culture that privileges some bodies over others (thin, male, cisgendered, heterosexual, white, able-bodied, healthy), how dangerous it can be to connect to our needs; to our own authentic experience of ourselves.

I hope it might make sense then, why I’m categorizing “self-optimization” with the survival strategies of disconnection.

The essential message of “self-optimization” is that we must make a conscious effort to manage ourselves. We can’t trust our bodies to tell us when to rest or what to eat; that our natural instincts are wrong; that we should impose new thought patterns on old ones, and make our bodies into different shapes, and control all natural impulses in every domain.

“Self-optimization” superimposes Western ideals of rationalism and beauty over our inborn sense of what is right for us. In many ways, this feels to me like the most tragic of the disconnection strategies, because it masquerades as bodily autonomy while deepening the chasm that divides us from our embodied experience.

“Self-optimization" as a choice— and the alternative

I want to make it clear that I am not holding any judgement around the choices we make to manage our lives. All of the strategies in the blue column above are valid adaptations in a family, environment, or system that is fundamentally unwell.

We should remember, too, that these strategies are how many of us manage to cling to hope for love, or a benevolent universe. If we have to acknowledge the bleak reality-- that health/wellness in modern western society are only accessible for the incredibly privileged few; that our systems are not made to care for us— we risk complete despair and nihilism. Far easier to fall back on the idea that we are the problem and we just need to work harder to fix it.

I have engaged in all of these behaviors myself (and still do, in many cases). But I also want to hold the possibility that we have other choices we can make— to reconnect our bodies, and our needs, and thereby to our authentic selves. To experience self-appreciation, self-trust, self-love, real autonomy and individuation. Even if we’ve learned to shame ourselves at every opportunity, we can start to question whether or not these strategies are still useful for us. Perhaps we start to find, as many people do, that we no longer need to shame ourselves in order to be accepted or loved. And while we may still need to operate cautiously in the world in order to be safe, we learn that we can do so by choosing to adopt a persona6— knowing that we still accept and value our authentic selves.

This is why the act of reconnecting to our sense of authentic self is so revolutionary. As we learn to trust ourselves-- resting when we need to, eating what our bodies ask for, recognizing that our needs and desires are valid, and that we deserve to have them met-- we can meet our external circumstances in a more honest way.

The alternative to “optimizing” ourselves is to trust ourselves.

But what about love in the universe?

In my experience— and in Jung’s formulation— it is the choice to trust our own experience that leads to an authentic spiritual experience. In fact, connecting to the “small-s” self was the only way to really connect to the capital-S “Self;” our understanding of a “God-image,” which he says is “inwardly experienced… an ever-present archetype from which man cannot escape.”7

As children, it is natural that we conflate our experience of our caretakers with that of a “God-image.” As we mature, however, and are able to make a choice to trust ourselves as being inherently worthy, we find that we are more than a reflection of others’ perception of us. It takes a profound sense of self-trust to let go of the idea that we are shameful; that we must work effortfully to manage ourselves through “self-optimization;” but as we disconnect from the collective (external, societal) ideas about who we’re meant to be, we are rewarded, as James Hollis says below, by finding that we have available energy when we practice authentic connection through the feeling function:

“The feeling function tells us whether something is right for us or not. Unfortunately, many of us have long ago lost contact with this resource and even deliberately override its directives in order to be productive. We do not choose feelings; feelings are autonomous, qualitative analyses of our life. We can only choose to make those feelings conscious, and then decide whether or not to act on them… If what we are doing is right, the energy is available….Too often we are obliged to channel our feelings and our energy into a soulless task. We learn to do this because we are rewarded for it and would feel shame if we stopped.”8

We are, in fact, Jung reminds us, related to “something infinite:”

“The decisive question for man is: Is he related to something infinite or not? ... Only if we know that the thing which truly matters is the infinite can we avoid fixing our interests upon futilities…He experiences himself as something that is thrown into existence for a purpose; and this gives him the capacity to endure.”9

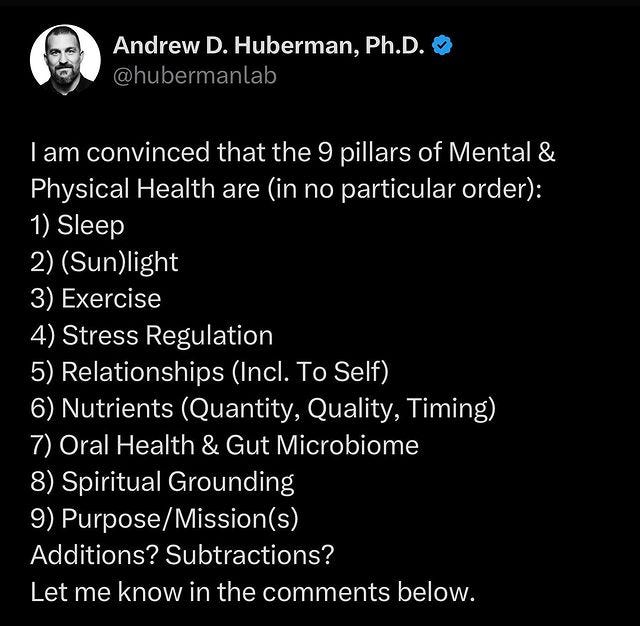

You may not be familiar with Andrew Huberman, but someone you know probably thinks he’s the smartest dude ever. Slightly scandalous but very popular super-science-bro has a wide variety of guests on his podcast, from Jordan Peterson (that’s a “no thanks” from me) to James Hollis (one of my faves). So, mixed bag situation. Huberman is famous for this kind of message:

Some of these were really great. Others? I’d love my money back. But I can’t say I haven’t learned a lot.

Athletic Greens, who, at least for a while, along with “Better Help,” sponsored every podcast you ever listened to. And I liked them! Even my dog liked Athletic Greens. But at more than $90/month, I finally had to admit it was probably not doing anything. But oh, how I wanted them to work. RIP, my love affair with Athletic Greens.

This is Huberman’s made-up term for yoga nidra, which I included to make myself giggle. I love yoga nidra. And all of his protocols are mostly great, I guess. But they’re not a substitute for paying attention to what my body/psyche are actually asking for.

Jung, C. G. Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Volume 11: Psychology and Religion: West and East. Translated by R. F. C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1958. §144.

Jung, C. G. (1970). Psychology and religion: West and East (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.; 2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1958)

Hollis, J. (1996). Swamplands of the soul: New life in dismal places. Inner City Books.

Jung, C. G. (1963). Memories, dreams, reflections (R. Winston & C. Winston, Trans.). Pantheon Books.

Amazing article, as always. This line in your article really hit hard: ‘We create a fantasy that if we can just manage ourselves properly, we’ll get the love and the care we need.’ I love James Hollis, and while I haven't read the book itself, I had come across a quote from Hollis’ book, The Middle Passage, which rung true as I read your piece today - ”In the end we will only be transformed when we can recognize and accept the fact that there is a will within each of us, quite outside the range of conscious control, a will which knows what is right for us, which is repeatedly reporting to us via our bodies, emotions, and dreams, and is incessantly encouraging our healing and wholeness” -- as someone who has a jar of Athletic Greens growing old in the fridge, everything you said really resonated on so many levels - sometimes I fall prey to marketing that claims that this pill, powder, green juice, workout, etc will be the thing to finally “cure” me, but I realize I'm still far from it.

Thank you, Laura, for expressing how we blame, shame, and sabotage ourselves. I read "Swamplands of the Soul"; it's a great book!