Taming the Protective Complex

Why do some of us fail to "get better" despite all our inner work? Our most feral, protective complexes hold the key to our wellbeing-- & they desperately want our attention.

“Whenever there’s ambivalence—and there almost always is when we’re dealing with human beings—it’s important to understand the other part that can only speak in the code of symptoms and strategies.”

-Dr. Laurence Heller1

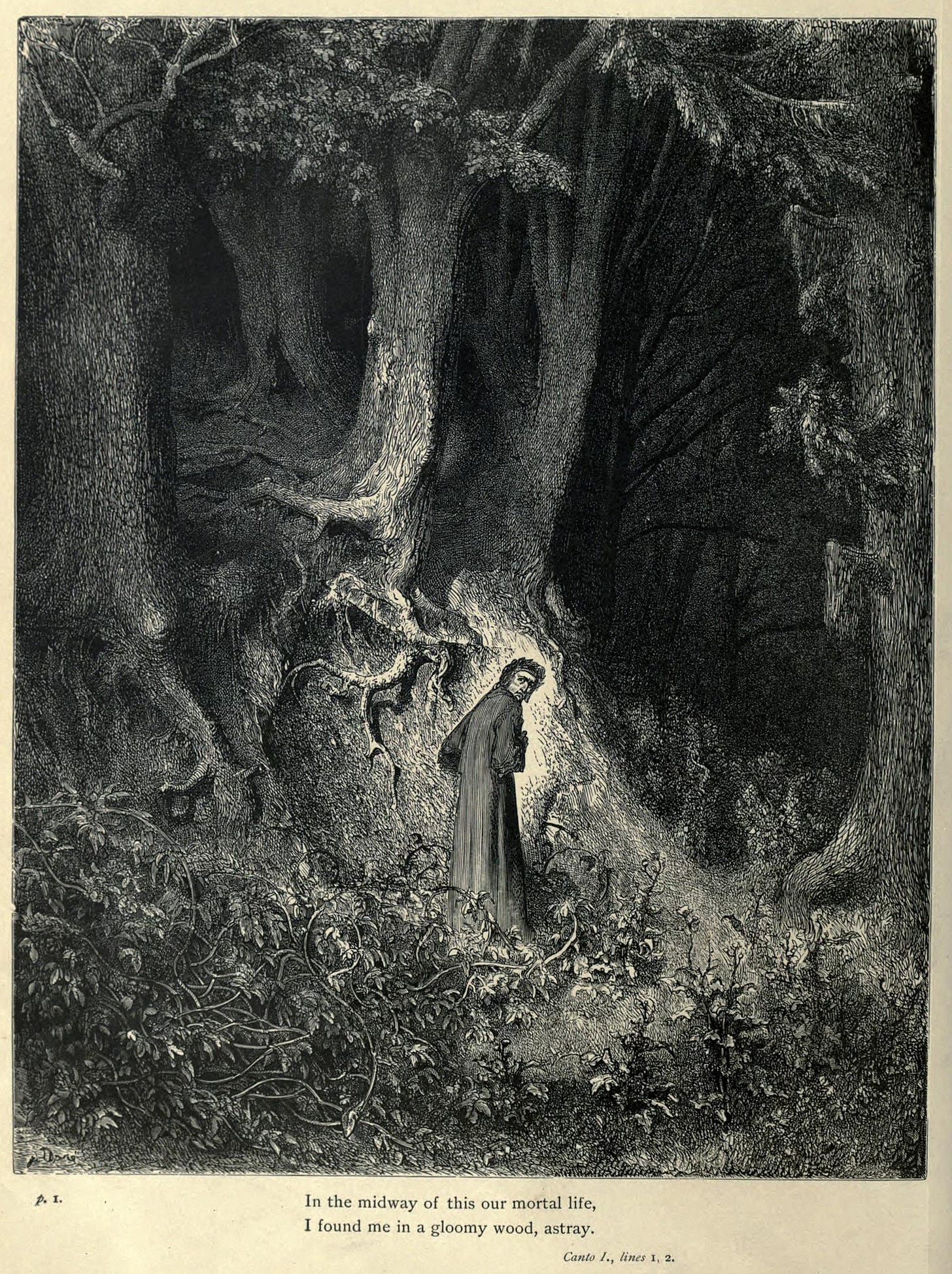

My analyst leaned into her Zoom screen. “I think,” she said, “you need to remember what is inscribed across the gates of Hell: Abandon All Hope, Ye Who Enter Here.” Then, in case this was unclear, she added, “You need to give up hope that things are going to get any better.”

I sat back and took this in. I had just described, in painful detail, the experiences of the past few weeks, in which I’d struggled mightily with my experience of grad school. "I really feel that I have given up hope,” I said. “I don’t think it’s going to get any better. So why do I need to keep talking about it?”

What was it, in me, that was so unhappy that it couldn’t simply “give up hope” and accept things as they are?

The importance of recognizing our discontent

Most spiritual or religious teachings frame discontent as something to be overcome. Whether it’s through trust in God, or Allah, or a recognition that dukkha (suffering) arises attachment and desire, we learn that to be content, or grateful, is a higher moral path.

These teachings are necessary because discontent is a primary human experience. When infants are hungry, afraid, or in pain, they cry to express our discontent— they only way they can get their needs met. As we grow, we internalize teachings from our family, environment, and culture, about what we are allowed (or not allowed) to want or need. We push down our unhappiness, direct it inward or outward; we blame others or we shame ourselves. In other words, we form a complex around this process, which, as Dr. Heller says, erupts in “the code of symptoms and strategies.”

“A ‘feeling-toned complex’… is the image of a certain psychic situation which is strongly accentuated emotionally and is, moreover, incompatible with the habitual attitude of consciousness... [I]t has a relatively high degree of autonomy, so that it is subject to the control of the conscious mind to only a limited extent, and therefore behaves like an animated foreign body in the sphere of consciousness.”

—Jung, CG, A review of the complex theory, emphasis in the original2.

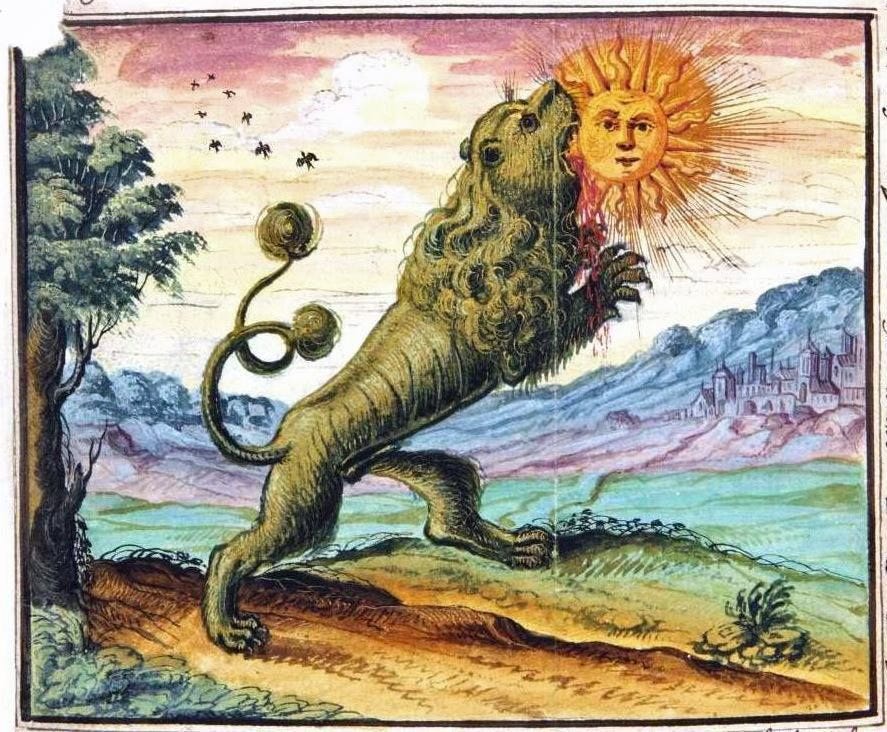

These young, unhappy parts of us that we’ve splintered off— our deepest discontents— form autonomous complexes that behave like an “animated foreign body.” Unacknowledged and disallowed, they live like wild beasts, roaming freely in the shadow of our consciousness. When something happens that we don’t like, we might consciously say, “that’s okay.” But we find ourselves complaining incessantly when we don’t mean to; or flying into a rage at the smallest provocation; we cry suddenly, for “no reason;” we may feel deep shame around our needs, or develop physical symptoms like stomachaches, or migraines. These reactions might feel very dissociated, or young, or immature, because they belong to a part that has never been allowed to develop.

“I can’t let myself be like the sun.”

“A girl aged 12 made, with her eyes closed, a sun (out of clay). As the sun she smiled (a rare occurrence for this child), and talked about how she warmed everyone and was bright and shiny. When she finished talking she resumed her usual scowling facial expression. When I asked her if she ever felt like the sun in her real life, she said, ‘No! I can’t let myself be like the sun. If I do, ,everyone will think things are good in my life and nothing will ever change.’”

—Oaklander, V., Hidden Treasure: A Map to the Child’s Inner Self3

When I read this passage, I had to stop, and read it again. It felt like the story of my life, and of so many of my clients’ lives. I lived under a cloud of heavy depression for most of my young life. The glass was perpetually half empty, if I could even acknowledge the liquid at all. Because my own needs were unmet, and I had no idea how to address them, I turned that discontent inward. In my world, there was no sun.

I’d had tons of therapy, but it was meditation that made the biggest difference for me. I remember a crystal-clear moment in which I actually felt for the first time that I had a choice around a response. I could be depressed, but I didn’t have to. Yet even after that, as more and more satisfaction seeped into my life, I resisted acknowledging it to others. If someone asked me how I was doing, I was afraid to say, “not too bad.” Not, as you might think, because I was afraid I might feel worse again— but because, like Violet’s 12-year old above, I didn’t want people to “think things are good in my life.” I needed more external acknowledgement, validation, that I was facing challenges. That things really weren’t “good” yet.

Freud & “resistance”

It’s quite common in the wellness world to speak about individuals who are “resistant,” or “non-compliant.” This kind of language is unnecessarily pathologizing; it doesn’t acknowledge that the “resistance” is itself a symptom of the client’s attempts to heal. Freud was the first to write about this phenomenon:

“There are certain people who behave in quite a peculiar fashion during the work of analysis. When one speaks hopefully to them or expresses satisfaction with the progress of treatment, they show signs of discontent and their condition invariably becomes worse.”

—Freud, S. The Ego and the Id.4

Marcus West suggests that rather than thinking of these individuals as “resistant,” we should recognize that

“they ‘know’ that the trauma has not been sufficiently recognized, addressed, or worked through. There is a profound way in which the individual who experienced significant early relational trauma remains true to this trauma, despite its current destructive consequences, and they cannot bear for certain elements to remain unknown; it is as if they cannot bear to abandon their infant self which originally experienced the trauma.”

—West, M., Into the Darkest Places5

This is especially critical when we consider that in the United States, at least, in a managed-care system (such as insurance, or Medicaid), our current mental health system sets a precise limit on the number of sessions that are allotted. Providers with the best intentions may find themselves pushing their clients to admit that they’re “better.” Depth approaches are discouraged in favor of short-term therapies that address symptoms quickly. And all the while, the external oppressive circumstances that contribute to negative mental health continue unabated, and often unacknowledged. Is it any wonder that clients will continue to “resist,” consciously or unconsciously, when they know their underlying needs are not being addressed?

The “resistance” of protective complexes

In my work with clients, I have learned to watch for what I think of as their “protective complexes.” The ones that, like Violet Oaklander’s 12-year old client, know they need to make sure I know “things aren’t good in my life.” Or the clients who need to tell me, before we do anything physical, that they “aren’t feeling very well today.” Or who express concern that lifting that kettlebell might be “too heavy.” Or those who immediately start yawning, or whose eyes glaze over, or who suddenly feel very sad, when we start a new activity. Or the client who, upon receiving a compliment, expresses shame, or attacks themselves harshly.

All of these are, as Heller says in the quote at the head of this article, “symptoms and strategies” of a protective complex.

What would you do with a crying baby?

In any kind of helping profession— or even just with our family or friends—, it is tempting to try to convince, or cajole, or prove, to someone, that they are the strong, brave, healthy people we know they are, or want them to be. This may even have a temporary, positive effect— especially if, like most of us, that person has been conditioned to listen to external voices about what they can or should do. However, as Freud found, when we fail to acknowledge and validate their experience of discontent, fear, illness, or unhappiness, we are taking sides against a very important protective complex— one that will only grow stronger and angrier as a result.

If we think of these complexes like a crying baby, protesting to have its needs met, we can understand the importance of attending to the symptoms, strategies, and symbols they produce. We can look to Thích Nhất Hạnh for a spiritual approach that doesn’t deny our discomfort, but welcomes it:

“So the practice is not to fight or suppress the feeling, but rather to cradle it with a lot of tenderness. When a mother embraces her child, that energy of tenderness begins to penetrate into the body of the child. Even if the mother doesn’t understand at first why the child is suffering and she needs some time to find out what the difficulty is, just her act of taking the child into her arms with tenderness can already bring relief. If we can recognize and cradle the suffering while we breathe mindfully, there is relief already.”

― Thích Nhất Hạnh, No Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming Suffering6

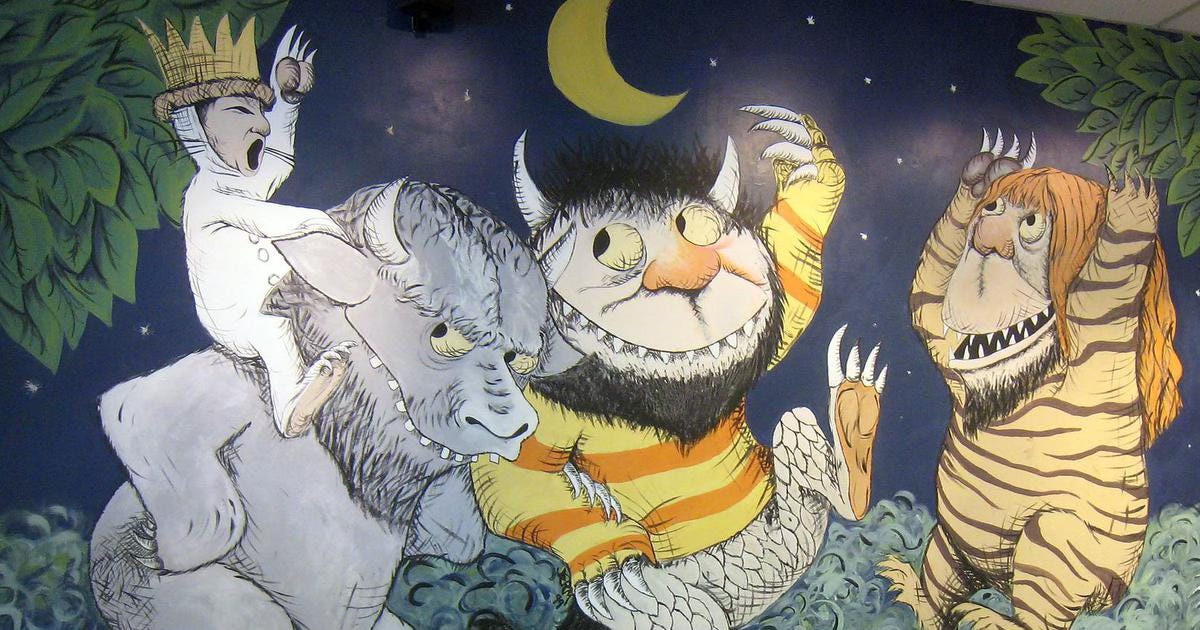

It takes a lot of courage and emotional maturity, as practitioners, to allow our clients’ pain and to encourage them to give voice to it. When we feel their suffering, it can feel that by allowing them to voice their pain, we’re not directly offering them “help.” But this is precisely what’s needed to bring the protective complex into consciousness, where it can be fully integrated. Left in the shadow, it is feral; devious; powerful and relentless. Like the monsters of Maurice Sendak’s Where The Wild Things Are, our complexes need to be fully acknowledged— looked in their yellow eyes!— before we can make them ours.

By giving our feral complex our full, respectful attention and allowing its voice to be heard (“You’re afraid that that weight might be too heavy for you;” or “It feels like you’re still not feeling as healthy as you’d like to,” or “You know you’ve made some progress, but you’re still experiencing quite a bit of sadness, too”), the “energy of tenderness begins to penetrate.”

This technique takes the pressure off of both parties— nothing needs to happen, or change, in that moment— but, in my experience, almost inevitably, something does begin to change, almost immediately, when the complex is acknowledged. “You know,” a client said to me last week, “Sometimes I think, ‘that’s more than I should do,’ and then I think, ‘I could just try it and see what happens.’ And then I can always do it!”

This is how we integrate the “wild things” that are our protective complexes, and make their feral energy ours.

“Abandon all hope, ye who enter here”

The week before that conversation with my analyst, I’d been raging with the anger, the injustice, the sheer mundane hell I’d been experiencing in my Master’s program— which is designed to prepare one to survive in the very clinical, non-depth-oriented, mental health world I find intolerable. Since the first semester, in which a professor declared, “We now know there’s no such thing as the unconscious mind. It’s all based on behaviors,” I’d been abandoning hope again and again.

But from time to time, something pushes my buttons. It’s not always the program itself, but, more likely, a different kind of complex of my own that says, “You should be able to deal with this better,” or, “Why are you so mad about this? It’s just how it is.” Perhaps even my well-intentioned analyst, in suggesting I give up hope, was pushing that button. This kind of complex— call it a gratitude complex, or a satisfaction complex— is based in the cultural training I received as a good girl growing up in our Protestant-work-ethic culture. It’s this complex that triggers the wild beasts of my own protective complexes, that make me want to scream, to complain, to say “It’s not fair, I’m not happy, THINGS ARE NOT OKAY.” Feeling this doesn’t mean that I’m not a good person, or that I’m a bad Buddhist— it means that I can turn, with tenderness, toward my emotion, and to recognize and cradle the suffering.

Looking at that image of Max riding the wild beasts, I remember reading the book as a kid. How scary those Wild Things were to me, and how incredible that he was able to tame them. Similarly, how outsized my own depression and rage and helplessness felt, unacknowledged and misunderstood. And how wonderful that I can use my big, angry, sad beasts now— turned friendly, loving, and utterly, fiercely protective— to create the kind of world I want to live in.

NARM® Training Institute. (2025, September 2). Working ambivalence: Why we don’t take sides (inner). LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/working-ambivalence-why-we-dont-take-sides-inner-ih1oe/

Jung, C. G. (1960). A review of the complex theory. In H. Read, M. Fordham, & G. Adler (Eds.), The structure and dynamics of the psyche (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.) (2nd ed., Vol. 8, pp. 92–104). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1934)

Oaklander, V. (2006). Hidden treasure: A map to the child’s inner self. Gestalt Press.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id (J. Strachey, Trans.). In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp. 1–66). London, England: Hogarth Press.

West, M. (2016). Into the darkest places: Early relational trauma and borderline states of mind. Karnac Books.

Thích Nhất Hạnh. (2014). No mud, no lotus: The art of transforming suffering. Parallax Press.

🧡🧡🧡🧡🧡🧡

Sitting with discomfort instead of denying pain creates a container to hold what might want to be pushed away. Cradling suffering with tenderness allows space for feelings to emerge without judgment. Such an important reminder, thank you, Laura.